by Shari

We recently received a question about learning to sit on the floor without support. Because we often write about the benefits of sitting on the floor (see To Sit or Not To Sit (on the floor)?), we thought having a little guidance for people who are currently unable to sit comfortably on the floor would be useful for a large number of people. So we decided to dedicate an entire post to the topic of how you can learn to sit comfortably on the floor. But let’s begin with the question:

Q: I’m a stiff Western guy who was brought up sitting on chairs and finds it really uncomfortable to sit crossed-legged on the floor even for a few minutes. Now I find that for my wedding, which will be a Hindu ceremony, I will be expected to sit on the floor for several hours. What can I do to get in shape for this? (My normal exercise routine includes running and weight lifting—I don’t do yoga yet at this point.)

First off, may I say congratulations on your upcoming wedding. How exciting for you, and you are to be complimented in your thoughtfulness for your desire to fully participate in your wedding's rituals. I don’t know anything about Hindu wedding ceremonies except what I have read about or seen in various movies but I do know that though you will be on the floor you won’t be totally motionless. What I don’t know is exactly what type of sitting posture you will be required to do for certain lengths of time. I would encourage you to discuss this with your fiancé but let us propose that you may be in kneeling or cross-legged positions all without external back support.

For you, and everyone else who wants to work on sitting without support, it might be helpful to break down the components of unsupported sitting. Which areas need to be both flexible and strong that you can work on during the upcoming months? We also need to discuss the role of breathing in enabling you to sit unsupported.

The vertebral spine and the diaphragm are major supporting internal structures of the human body. The spine consists of four curves that when properly stacked upon each other can withstand a significant amount of gravitational force to maintain the solidity of the curves. The curves allow the spine to move as well as to maintain stillness. Nestled deep within the pelvis—which connects the vertebral spine to the lower limbs/legs—is a very important bone called the sacrum. The sacrum and the two pelvic bones (ilia) are literally the bridge that forms the base of support that we need to sit. The femurs (thigh bones) connect into the ilia at the hip joint to widen the base of support. To sit unsupported in a cross-legged fashion, we need to provide good contact of the outer heads of our femurs (thighbones) with the ground.

There is a lot of discussion among health care professionals and yogis on what ideal sitting posture is and how to obtain it. But for our discussion we need to find you a doable position. The key is that when we sit unsupported we need to position our knees lower than our hips. This is easy to see when you sit in a chair without using the backrest. To obtain this position we typically need to raise our seat height up to widen the angle between our torso and our thighs. Typical chairs for standard height individuals have us sitting with our knees level to our hips and our torso perpendicular to the chair and this is termed 90/90 sitting position. But if we widen the angle of thigh to torso ratio to 135 degrees it is easier for us to lift up and lengthen our spines.

This is where I suggest you start. Place a pillow or folded blanket on the chair seat to raise your pelvis—this will allow your knees to be lower than your hips so your pelvis can roll over the head or your femurs (thigh bones) to re-establish your lumbar curve (your lower spine). Then you can lengthen or elongate your spine. This will help you learn to sit with your spine in a lengthened position and to support this posture from the “inside out.”

To learn how to stabilize the spine from the inside out we need to learn about our diaphragm, transversus abdominus, and pelvic floor musculature, and how they all assist in spinal stabilization, especially in a seated position.

The diaphragm is the dome-shaped sheet of muscle and tendon that serves as the main muscle of respiration and plays a vital role in the breathing process as well as internal stabilization. The origins (attachments) of the diaphragm are found along the lumbar vertebrae of the spine and the inferior border of the ribs and sternum. When we inhale, the diaphragm contracts and is drawn inferiorly into the abdominal cavity until it is flat. At the same time, the external intercostal muscles between the ribs elevate the anterior rib cage like the handle of a bucket. The thoracic cavity becomes deeper and larger, drawing in air from the atmosphere. During exhalation, the rib cage drops to its resting position while the diaphragm relaxes and elevates to its dome-shaped position in the thorax. Air within the lungs is forced out of the body as the size of the thoracic cavity decreases.

Structurally, the diaphragm consists of two parts: the peripheral muscle and central tendon. The peripheral muscle is made up of many radial muscle fibers—originating on the ribs, sternum, and spine—that converge on the central tendon. The central tendon, which is a flat aponeurosis made of dense collagen fibers, acts as the tough insertion point of the muscles. When air is drawn into the lungs, the muscles in the diaphragm contract and pull the central tendon inferiorly into the abdominal cavity. This enlarges the thorax and allows air to inflate the lungs.

|

| Diaphragm |

Due to its structural orientation, the diaphragm can be used to assist in torso stabilization for erect sitting along with contraction of the transversus abdominus muscle. The transverse abdominis muscle attaches to the thoracolumbar fascia and the deep erector back muscles between the pelvic bone and rib cage posteriorly and from the lower six rib cartilages, linea alba and the inguinal ligament anteriorly. It extends the entire length of the anterior trunk. Since it is the only abdominal muscle to attach to the posterior spine, it is considered the “human corset” of the trunk.

It is also helpful to work with your pelvic floor. The pelvic floor muscles create a hammock that spans the base of the pelvis from the front to the sides and to the back. Women often learn about these muscles after childbirth and are taught Kegel exercises to “strengthen” this area. You learn to engage the urogenital triangle without using the buttocks or tucking your tail to engage. In yoga mula bandha (root lock) is the “Kegel” and is taught to create strength and preserve energy of the body.

To learn how to feel the diaphragm and transversus abdominus, you can lie on the floor with your head slightly elevated and your chest opened. You can do this by folding three yoga blankets in an overlapping stepped or tiered position so the different layers of blankets support the curve of your lumbar spine, your thoraco lumbar junction and lastly your head (see Yoga Couch on gingergarner.com):

If this setup is too complex, you can try a Supported Savasana with your torso on a bolster (or folded blankets) and your head on a support. See Savasana Variations for info.

To sense the muscular actions of breathing, place your hands on the outer edges of your waist on your floating ribs. Gently firm and draw in the area just below your umbilicus and keep that area gently firm as you take a full breath in. As you inhale, notice if you can feel your lower rib angles moving out into your hands. As you exhale, continue to keep your lower belly engage as you feel your ribs return to their resting position. Once you can do this breathing in the reclined position, you can transition to doing it in hands and knees position and then to sitting in a chair to learn to create internal support in an upright position.

To learn where your pelvic floor is, sit on a soft but firm chair with your knees lower than your hips and gently bear down as in defecation. You should feel a slight bulging of your perineum. Then, try to lift your perineal area by tightening the muscles between your pubis and anus. You might also notice that you are drawing in your lower belly to do this, and that is okay because we often engage both our transversus abdominus and our pelvic floor muscles. Just make sure you aren’t tightening your buttocks to do this. Continue to practice this regularly while sitting in a chair until you have built up your tolerance and stamina.

Now let’s look at the more visually obvious muscles you need to work with. To sit erect for long periods of time—whether on a chair or floor—you need to have strong back muscles. These include deepest paraspinal msucles that run the entire length of your spine from head to tail, the deep spinal muscles that are longer and broader, and the more superficial larger back muscles, such as the latissimus dorsi, trapezius. A good way to begin to strengthen these muscles is by practicing simple backbends like Locust pose (Salabasana) with various arm positions and leg lifts (see Locust (Dynamic Version) for a few ideas) and Bow pose (Dhanurasana).

You might also want to work on your back in Bridge pose variations (Setu Bandha Sarvangasana), especially working with the deep spinal stabilizers, which you can do with One-Legged Bridge or Marching-in-Place Bridge. You might want to have someone watch you when you do these positions to make sure that you can keep your spine neutral and not sag or twist. Also an all-fours position (see Hunting Dog Pose) with opposite arm and leg lifts will work the deep spinal stabilizers. Using a stick that is placed from your head to tail along your spine gives you nice feedback that you are maintaining a neutral spine. Please remember when you start doing these active training positions to use your deep abdominal/diaphragmatic /pelvic floor stabilizing breathing that was described earlier.

Next let’s look at flexibility of your spine. Begin with passive backbends that are nice and easy, such as lying over a bolster to arch your spine into a reverse “C” curve. Keep it gentle—don’t be too aggressive in increasing your arch. More is definitely NOT better. Work with nice deep belly breaths here, not your stabilizing breathing pattern. Cobra pose (Bhujangasana) is also a good way to build spinal flexibility as well as a gentle Cat/Cow pose.

Now it’s time to turn to the lower body and learn to stretch our hips, buttocks, and legs. Thread the Needle/Figure Four pose (Sucirandhrasana) will help you begin to stretch your tight outer hip muscles. Happy Baby Pose (Ananda Balasana) will also help begin to stretch your gluteal muscles and tight lower back fascia. You can practice version one of Reclined Leg Stretch (Supta Padangusthana), but you may find that a sustained single leg stretch through a doorway with one leg up the doorway and the other leg straight on the floor through the doorway is a nice way to hold a hamstring stretch for a longer time period without your hands getting tired gripping a strap. Different poses to stretch your hip rotators such as seated Cow-Face pose (Gomukasana) or Pigeon pose (Kaptosana) preparation are also helpful. To stretch your rhomboids (mid-back muscles), consider adding upper back stretches, such as Garudasana (Eagle pose) arms, to your seated poses.

Finally, we need to move to standing. Begin at the beginning with Mountain pose (Tadasana). You need to learn to stand erect first before you can sit erect.

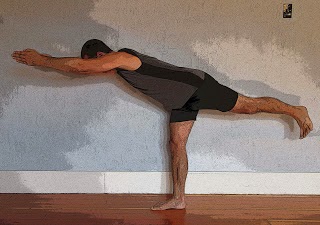

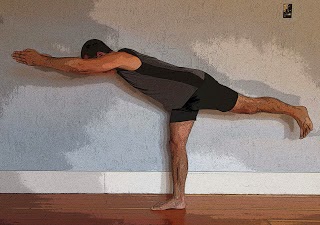

From here, learning to do Half Downward-Facing Dog pose at the Wall begins to teach you how to integrate your arms, legs and torso.

Then we do have to move onto standing poses! I think by this time you may realize that it would be helpful for you to join a beginner yoga class and to learn to do a home practice. When you find a class that you like, I would recommend privately talking with the teacher and perhaps meeting with him or her to help you devise a doable home practice to target all the areas that you need to stretch and strengthen. With patience, perseverance and a sense of humor you will accomplish your goal!

recomended product suport by amazon